Introduction

For many years data scientists have studied performance

streaks in sports. Research on the “hot

hand,” for example, has attempted to identify whether positive performance

streaks will drive further success on subsequent plays.[1] Is a basketball player on a scoring streak

more likely to make her next shot? Is a

baseball player more likely to get a hit after several hits in a row? Is a volleyball attacker more likely to get a

kill after multiple successive kills than after multiple successive misses? Belief in the hot hand is common and the

nature of serial performances has been studied across a multitude of sports.[2]

Research has found limited empirical

evidence for a hot hand phenomenon, however, leaving most data scientists to

conclude there is little continuity between successful prior and subsequent skilled

performances in sport.[3]

While hot hand research is abundant the implications of negative

serial performances are less well known.

Here we analyze not performance following success but rather performance

following failure -and specifically whether prior failure drives

subsequent failure in sports performance.

This “cold hand” analysis has received minimal scholarly attention and

the analysis we undertake here is entirely novel.[4]

We consider the “cold hand” phenomenon in the context of

receiving serve in beach volleyball. Our

hypothesis is that serve receive players are more likely to pass out of system

immediately following an out of system pass than immediately following an in system

pass. We anticipate that failure in

serve receive will predict further failure in serve receive by the same player

on the next opportunity when not interrupted by a timeout or a break between

sets.

To gain further insight into how players perform we studied

players’ performances according to experience and pressure variables.

Experience

To determine the influence of experience we analyzed the

data according to players’ graduate years.[5] We hypothesized that players’ experience would

be influential in predicting their likelihood of exhibiting negative

performance dependence habits. We

expected the “cold hand” phenomenon (if we found one) to be greater among

freshmen than among seniors. In other

words, we expected the general likelihood (if we found one) of players to pass out

of system following an out of system pass would be magnified in freshmen and reduced

in seniors.

Pressure

To examine the impact of pressure on performance we examined

serve receive data according to pressure variables associated with game

conditions. We hypothesized that the

impact of prior performance failure would be situational but would be magnified

during times in the game when players perceived the greatest need to perform

well. We predicted that players more

likely would pass out of system following a previous out of system attempt when

the performances occurred near the end of the game and particularly if the

player’s team was behind in the score. Informed

by prior literature on the confluence of performance and pressure,[6]

we anticipated that anxiety induced by (i) prior failure and (ii) situational

game conditions would impair performance and contribute to an increased

likelihood of continued out of system passing.

Experience and Pressure – Interaction Effect

Lastly, we explored the interaction effect of the experience

and pressure variables. We hypothesized

that negative performance dependence would appear most predominantly when game

conditions required the players with the least collegiate experience to perform

under the most pressure.

Implications

The novel analysis we undertake here has implications for

beach volleyball tactics and training.

Serving the player who most recently passed the ball out of system is a

common beach volleyball tactic. If

performance is dependent - out of system passing portends further out of system

passing - then serving the most recent underperformer could result in the optimal

strategy being utilized. But if

performance is not dependent then continuing to serve the same player would have

to be justified by reference to some other strategic consideration than

reception efficacy. Data showing that

poor reception efficacy reduces the effectiveness of offensive scoring in beach

volleyball suggests that the decision of who to serve in this context has

important implications.

For players and coaches our research could improve

understanding of the psychological processes at work when athletes in serve

receive perform following failure.

Understanding post-failure performance can further the development of

training protocols and interventions designed to enhance failure recovery in athletes

- a skill whose value is heightened in

beach volleyball where athlete substitutions are not permitted and performance

under pressure is necessary to success.

METHODS AND PROCEDURE

The purpose of

this study was to assess whether players receiving serve in beach volleyball

are more likely to pass out of system immediately following an out of system

pass than following an in system pass and to identify whether and how experience

and pressure variables influence performance following failure.

Data

Characteristics

We analyzed 55,125

reception attempts by 690 different college beach players during five

collegiate beach volleyball seasons from 2016-2020. We observed a total of 783 matches and 1,766

sets, of which 1,558 were 1st and 2nd sets in a match and

208 were deciding third sets. Players

whose performances were analyzed competed on 41 different NCAA beach volleyball

programs, 34 of which compete in NCAA D-I, 6 of which compete in NCAA D-II and

1 of which competes as a member of the NJCAA.

Data Compilation

Data were compiled

from official matches during the championship segment of the college beach

season. Non-championship competition and

exhibition flights were excluded. Season

by season data on observed reception attempts, numbers of matches and unique

players are displayed in Table 1. The

distribution of players by class year is displayed in Table 2.

Table

1. Observed Reception Attempts, Matches

and Unique Players: 2016-2020

^Number of unique players is for the season indicated. Total number of unique players is 960. The total number of players represented in the study is 1,125.

Table

2. Unique Player Distribution By Class

Year: 2016-2020.

Plays from which

performance dependence could not be analyzed were excluded, including each

player’s first reception attempt in each set.

Receptions immediately following team, technical, media, medical and

officials’ timeouts were excluded, as were consecutive receptions separated by

an intervening service error, due to the passage of time between the attempts. We chose to include consecutive reception

attempts during intervening (i) side changes by teammates (players choosing to alternate

between one or the other sideline) and (ii) side switches by opponents (pairs

switching sides of the net as required by rule) due to the brief duration of

time involved in those routine movements.

Plays from which

performance dependence could not be analyzed were excluded, including each

player’s first reception attempt in each set.

Receptions immediately following team, technical, media, medical and

officials’ timeouts were excluded, as were consecutive receptions separated by

an intervening service error, due to the passage of time between the attempts. We chose to include consecutive reception

attempts during intervening (i) side changes by teammates (players choosing to alternate

between one or the other sideline) and (ii) side switches by opponents (pairs

switching sides of the net as required by rule) due to the brief duration of

time involved in those routine movements.

Data Coding

From 55,125 observed

reception attempts we identified 17,439 “sequences” of receptions for analysis. A sequence was

defined as two consecutive serve receive attempts by the same player in the

same set without an intervening game break or opponent service error. Each sequence was marked for reception

efficacy according to nine possible outcomes:

IS-IS, IS-OS, IS-A, OS-IS, OS-OS, OS-A, A-IS, A-OS, A-A. [7] Each reception and sequence was coded by (i)

the identity of the player, (ii) the player’s class year, (iii) reception efficacy

(IS, OS, Ace), (iv) score in the game, (v) whether the player’s team was

winning or behind, and (vi) phase of the game by side-change.

Reception Efficacy

and Failure

Characteristics of

“in system” (IS) and “out of system” (OS) receptions, and of reception errors

(A), were identified prior to the start of data collection. Quality control measures were undertaken among

data collectors to ensure consistency and agreement in efficacy rating of the receptions.

Pressure Variable

We measured

pressure according to three variables – (i) closeness of the score, (ii)

whether the reception player’s team was ahead or behind, and (iii) phase in the

game. We predicted that pressure was

greatest when conditions in the game amplified the athletes’ perceived

importance of performing best, i.e. when the score was close, which we defined

as a 3 or less point differential, when the receiving team was behind, or when

the game was nearly over, which we define as in the final side-change.[8] We assigned a cumulative point value to each

of these variables resulting in a total pressure scale ranging from 0 (lowest

pressure) to 3 (highest pressure).[9] Each reception attempt was assigned a

pressure score according to the scale.

Experience

Variable

Experience was inferred from the class standing

associated with each player. Class standing

was obtained from the websites of the schools for which the players were

competing. For players competing in

multiple seasons class standing was updated and linked to each player’s then

current performance.

Uncontrolled

Variables

Variables implicit in beach volleyball and not controlled

for in this study include: (i) wind speed and direction, (ii) temperature,

(iii) wet or dry conditions, (iv) type, inflation and weight of the ball, (v)

position of the reception teams, (vi) characteristics of the serve (speed, type

and angle), (vii) characteristics of the server (handedness and location), and

(viii) overall reception efficiency of each individual player.

Service Reception

- Choice of Performance

We chose to examine service reception because of its’ prominence

in the game. The ability to receive

serve well in beach volleyball drives successful offenses. At the same time serving strategies regularly

emphasize the need for repetitive passing performances. A common serving strategy, for example, is to

“target” one player to receive the majority of the serves. The more the targeted player underperforms

the more serves she will receive both overall and consecutively. Beach volleyball strategy thus places a

premium not just on repetitive serve receive excellence but also on failure

recovery – the ability psychologically to move on to the next play and perform

immediately after failing.

Receiving serve also provides a more controlled

environment for the study of performance dependence than many of the interactive

skills previously studied. Siding out in

volleyball,[10]

scoring in basketball,[11]

winning rallies in tennis[12]

and achieving hitting streaks in baseball,[13]

for example, all have previously been studied in the literature. All are associated with high levels of interaction

among competitors and changes to defensive strategies that mask whether

performance variations are attributable to dependence or other confounding

variables. Service reception, on the

other hand, is a skill performed by a single player without the assistance of teammates

and independently of a defense. It thus

represents a less dynamic and more appropriate environment for the study of

performance dependence than other skills.[14]

RESULTS

Effect of Failure on Performance

Out of System Reception

Analysis of 17,439 series of receptions indicates that failure

in serve receive negatively influenced performance on the subsequent play by

increasing the likelihood that the next ball would be passed out of system. Our results are evidence that negative

performance exhibits dependence and are suggestive of a cold hand in beach

volleyball reception.

College beach volleyball players passed out of system 18.14%

more often following an out of system pass than following an in system pass - a

statistical disparity greater than expected by chance or by players’ base

passing rates. We refer to this tendency

as the “Failure Effect” and will use the Failure Effect as our baseline to

assess the impact of experience and pressure on performance in subsequent

sections.

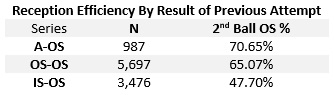

Table 3 shows that 65.84% (n= 6,684) receptions were out

of system after an out of system reception (OS-OS) while 47.70% (n=3,476) receptions

were out of system following an in system reception (IS-OS).

Table 3. Reception Efficiency Following Success and

Failure.

Effect of Reception Error

The negative influence of aces on future performance was

even more significant than was the influence out of system passing. Players were 5.58% more likely to pass out of

system after getting aced (A-OS) than if they had previously passed out of

system without being aced (OS-OS). When

compared to series in which players received the first ball in system, the

negative influence was even more significant.

When players were aced on the first reception attempt (a subset of out

of system passes), they were 22.95% more likely to pass the next ball out of

system. Complete data is shown in Table

4.

Table 4. Effect of Reception Error on Next Ball Reception

Efficiency.

The effect of reception errors on future performance has tactical implications for serving. The data suggests a significant advantage to serving a player who was aced on the previous play, but we repeatedly observed a less optimal approach. Our data show that in nearly 5 out of 10 serves following an ace the serving team missed the next serve (13.3%) or served to a location from which the other passer received the ball (32.8%).

Interpretation of Results

While we found evidence for negative performance

dependence in reception overall this should not be interpreted to mean that

every player exhibited this habit. We

found evidence only for performance decrease following failure among players on

average. The extent to which any

individual player received serve independently from influence of her prior

attempt requires a distinct statistical analysis and is the subject of a

forthcoming paper on that topic. In

terms of aggregating performances for purposes of analyzing the effect of

failure among performance streaks our approach is consistent with at least two

previous studies on negative performance dependence in sport.[15]

Figure A. Influence of Prior Reception on Likelihood of Out of System Passing.

Effect of Experience on Performance

To determine the

impact of experience on negative performance dependence we analyzed serial

passing attempts according to players’ class standing. We hypothesized that experience would be

influential in predicting whether prior failure in reception would lead to

further reception failure. While we

found that freshmen most often exhibited negative performance dependence - a

result we predicted – juniors were least effected by prior failure – a result

we did not anticipate.

Freshmen players,

with the least experience, were the most adversely affected by prior reception failure. Freshmen passed 64.86% out of system

following an out of system pass compared to 46.86% out of system passing following

in system passing. Juniors exhibited the

least negative performance dependence with 64.16% OS-OS reception compared to 49.19

% IS-OS reception. Complete data for all

players across class standings is displayed in Table 5.

Table

5. Reception Efficacy Following Success

and Failure by Experience.

Figure B.

Reception Efficacy Following Success and Failure of Previous Attempt by Experience.

Effect of Pressure

on Performance

To gauge the

impact of pressure on performance serial passing attempts were analyzed according

to several pressure variables related to game conditions. In doing so we were informed by a rich body

of research on the effect of anxiety on athletic performance. For many athletes competition

magnifies the importance of performing well and creates varying levels of

anxiety that paradoxically impairs the ability to perform at a time when

players want most to succeed.[16] We thus anticipated that pressure would

magnify the extent to which beach volleyball players exhibit negative

performance dependence in serve reception.

We further anticipated that the influence of pressure would fluctuate

throughout competition but would be most impactful when athletes perceived the

greatest need to perform well.

Pressure was

measured according to three variables – (A) closeness of the score, (B) whether

the passer’s team was ahead or behind, and (C) phase in the game. Each pressure variable was assigned a value

of +1 point on a cumulative scale and each reception attempt in a series was

assigned a pressure score from 0 (lowest pressure) to +3 (highest pressure) according

to the game conditions at the time of the attempt. Pressure

is characterized as “Low Pressure” (Score of +1), “Moderate Pressure” (score of

+2) and “Highest Pressure” (score of +3).

Data were analyzed for the main and interaction effects of each

pressure condition on reception following failure.

Overall, college beach players exhibited heightened negative

performance dependence under pressure and that effect was magnified as pressure

increased situationally. Complete data are

shown in Tables 6 and 7.

Pressure

– Main Effects

As expected, pressure had a significant effect on reception

following out of system passing. The average

effect of a Low Pressure condition was to increase the Failure Effect from

18.14% to 28.07%. Across all three

pressure variables, playing from behind had the largest negative impact on

performance. Players receiving serve

while behind in the score were 31.35% more likely to pass out of system

following an out of system pass compared to in system pass.

Pressure attributed to the impending end of the game had

the second largest impact on reception following failure. On the final side-change, players experienced

a 26.32% greater likelihood of repeating out of system passing.

Receiving serve while the score was close had the least

effect on player performance. When the difference

in score was 3 points or less players were 25.58% more likely to follow an out

of system pass with a second out of system pass.

Figure C. Likelihood of out of system reception

following out of system reception (OS-OS) compared to

out of system reception

following in system reception (IS-OS) under various Low Pressure conditions.

Our findings could be interpreted to suggest that anxiety

most impairs performance following failure when players are behind in the game. A possible explanation for this could be that

playing from behind is uniquely anxiety producing in a way that the other

pressure conditions - a close game and the end of the game - are not (necessarily),

such as when the score is tied early (e.g., 2-2) or the receiving team is

winning by a large margin late (e.g., 19-10).

In other words, players might always feel pressure when they are behind

but not necessarily feel pressure in a close game or late in the game.

Table 6. Main Effects of Pressure Variables on

Post-Failure Reception (PFR) – Low Pressure.

Pressure – Interaction Effects

Moderate Pressure

The interaction effects of Moderate Pressure were even

more significant than the Low Pressure conditions. Moderate Pressure refers to game conditions

during which two pressure variables existed.

Moderate Pressure, resulting from the interaction of multiple pressure

conditions, increased the incidence of back-to-back reception failure by an

average of 20.59%. Complete data is

displayed in Table 7.

Among Moderate Pressure conditions, (B) playing from behind

(C) near the end of the game had the largest negative impact on performance. Players receiving serve while behind in the

score near the end of the game were 41.28% more likely to follow an out of

system pass with a second out of system pass.

Pressure attributed to game conditions of (B) playing

from behind (A) while the score was close had the second largest impact on

reception following failure. When the

score differential was 3 points or less with the receiving team behind, players

experienced a 37.51% greater incidence of repeating out of system passing.

Receiving serve (A) with the score close (C) during the

last seven points of the game had the least negative effect on

performance. Players receiving serve

under these game conditions showed a 36.59% increased incidence of passing out

of system after doing so on the previous play.

Table 7. Interaction Effects of Pressure Variables on

Serial Reception Attempts – Moderate Pressure.

Highest

Pressure

The three-way interaction effect of (B) being behind by (A)

a close score (C) late in the game created the Highest Pressure condition and

predictably impaired reception performance the most. Under the Highest Pressure there was a 29.60%

increase (to 47.74%) in the rate of out of system passing following reception

failure on the previous play. Given the

number of co-incident variables, the Highest Pressure condition was relatively

rare in the game and represented only 5.63% (n=982) of the observed reception

series.

There was a 47.74% greater likelihood that one out of

system pass will be followed by another at the highest level of pressure

compared to 38.73% under Moderate Pressure and 28.07% under Low Pressure conditions

(average of 3 Low Pressure variables).

The influence of pressure on reception performance is evident in the

increasing difference between post-failure and post-success plays across

increasing pressure conditions.

Figure D. Likelihood of out of system reception

following out of system reception (OS-OS) compared to

out of system reception

following in system reception (IS-OS) under Moderate and Highest Pressure

Conditions.

Interaction of

Pressure and Experience

We next analyzed

the data to determine whether pressure’s impact on performance would vary with

the experience of the players. We

predicted that the Highest Pressure would most adversely impact performance by the

least experienced players. In particular,

we expected that if performance exhibited dependence then failure in serve

receive would predict further failure on the next play and that trend would be

influenced both by the experience of the players and the level (or type) of

pressure in the game.

Overall

The data indicate

that players at every level of experience showed a performance detriment under

pressure. From freshmen to graduate

students, pressure nearly doubled the incidence of out of system passing

following failure (OS-OS) compared to out of system passing following success

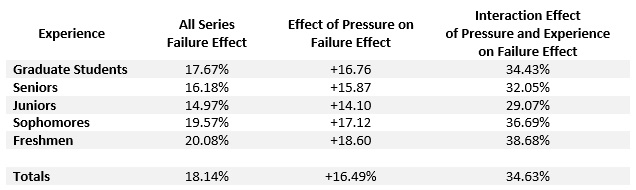

(IS-OS). Table 8 reveals the average effect of all

pressure conditions on performance across each level of experience.

Table

8. Average Effect of Pressure Conditions

by Experience.

Freshmen and sophomores

were most impacted by pressure in the aggregate, experiencing an average 18.60%

and 17.12% increase in post-failure out of system passing, respectively. Freshmen under pressure were 38.68% more

likely to pass out of system following an out of system pass than following an

in system pass while sophomores were 36.69% more likely to do so.

Juniors were

least impacted by pressure overall, experiencing 29.07% more out of system reception

following failure than following success. Seniors

and graduate students were moderately impacted by pressure overall, with data

indicating seniors were slightly less affected than graduate students. Under pressure, seniors were 32.05% and

graduate students were 34.43% more likely to pass out of system following

failure than following success.

Figure

E. Interaction Effect of Pressure and Experience on Post-Failure Reception

Performance.

Impact of Pressure

By Experience Level

While pressure

degraded performance regardless of the experience of the players (at no level

of experience were players immune from pressure) the extent to which

performance declined did vary by experience and pressure level, with some

classes showing a greater vulnerability to certain types of pressure than

others.

Table 9 reveals

the most and least impactful pressure conditions for each experience level. Not surprisingly, the largest effects were interaction

effects. The simultaneous co-incidence of

all three pressure variables – behind (B) by a close score (A) late in the game

(C) - is excluded because Highest Pressure uniformly had the largest negative

impact on player reception performance across all experiences levels and

occurred infrequently in competition – just 5.63% of all plays (n=982).

Table

9. Largest and Smallest Effects of

Pressure Variables by Experience of Player.

Graduate Students

Graduate students

were the third most affected by pressure overall, outperforming only freshmen

and sophomores, a trend perhaps owing to graduate students’ general lack of

experience in beach volleyball and specific lack of experience in reception. Graduate students were most likely to repeat

out of system passing when they were behind in a close game (A-B) and least affected

by pressure late in the game (C).

Seniors

Seniors, like

graduate students, were most affected by pressure when behind in a close game

(A-B) and least affected by pressure late in the game (C). Seniors outperformed graduate students,

however, in being less affected by pressure overall.

Juniors

Juniors showed

the greatest resistance to pressure overall compared to both the more

experienced and less experienced counterparts.

Juniors also outperformed their peers in reception efficacy following

failure in the Low, Moderate and Highest Pressure conditions. In line with seniors and graduate students,

juniors were most affected in reception following failure when behind in a

close game and least affected late in the game.

Sophomores

Sophomores showed

the second most vulnerability to pressure ahead only of freshmen, suggesting

that inexperience in college beach volleyball exposes players to greater

performance detriments under pressure.

Sophomores were most negatively affected by pressure while behind near

the end of the game and were least affected when the score was close.

Freshmen

Freshmen were

more negatively affected than their peers in the Low, Moderate and Highest

Pressure Conditions. The data show

uniformly that freshmen performance in reception following failure degraded

significantly under each pressure condition, lending support to our hypothesis

that inexperience would magnify the pressure effect on negative performance

dependence. Across pressure conditions,

freshmen showed the least performance decrement when the score was close and in

this respect resembled their sophomore peers.

Synthesis

Results show that

being behind in the score was the one constant among pressure conditions that

most adversely impacted performance across all experience levels. The results suggest a strategy, when ahead in

the score, repetitively to serve the player who previously passed out of

system, but our data show that nearly a quarter of the time (24.10%) that did

not happen. The extent to which this

phenomenon was due to serving skill or tactics is unknown. Informed by literature on the interacting

influences of fear, failure, anxiety and performance,[17] our

results may be informative in developing optimal serving strategies for

situational advantage in beach volleyball.

The data also

indicate a robust relationship between players’ experience and their

performance under pressure. Players with

the least experience (freshman and sophomores) exhibited the most significant

performance impairments under pressure.

Players with the most beach volleyball experience (seniors and juniors)

were least affected by pressure. The

correlation is not entirely causal, however, as juniors outperformed seniors in

pressure performance, a confounding result we did not expect.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of

this study was to determine whether performance exhibits negative dependence in

beach volleyball reception and whether experience and pressure magnify or

inhibit the trend. Negative performance

trends have previously been identified in professional football[18] and

golf.[19] The current study provides the first

indication that reception performance could exhibit negative dependence in

collegiate beach volleyball.

Our findings are tentative and novel. We found evidence overall that failure in one

play negatively influences performance on the next play in beach volleyball reception. Experience in the sport tended to mitigate

that effect and inexperience tended to magnify it. Experience alone, however, could not be

identified as a cause, as juniors outperformed all other classes in performing

best following failure – although they too were adversely impacted by their

previous performance. Whether the larger

performance decline of less experienced athletes can be attributed to greater

declines in confidence or self-efficacy, or whether the result is function of

motoric experiences,[20]

is a question for future research.

Pressure from game conditions magnified the effect of

prior performance failure as all players across experience levels suffered a

performance decrement under pressure.

While pressure differently impacted players by experience, all groups

shared a common characteristic of performing worst while behind in the game. Pressure tended to impact inexperienced

players most when they were behind near the end of the game. More experienced players tended to be most affected

while behind when the score was close.

Our methodology examined short series of two consecutive

reception attempts. This approach

increased statistical power through a larger sample size than analysis of

longer series would have produced. On

the other hand, our approach precluded us from discovering the extent to which

the prior failure negatively reverberated beyond the next play.

In line with prior research we aggregated our data from

all player performances – again in order to increase statistical power. We found evidence for a “cold hand,” i.e.,

that prior failure negatively impacts performance on the next play. We suspect, however, that the phenomenon is

not individually ubiquitous. Individual

players’ performances over time will best predict how they uniquely respond to

performance failure and will be the best evidence of how data can be used in

match preparation, for example. Our

study is just a starting point for analysis of the question. We think the future of research is in individual

predictive analysis based on individual performance habits. Coaches then can utilize those results as an

adjunct to advanced scouting closer to match day and compare the results

obtained from each source for disagreement or congruence.

The present study could be read to suggest that college

beach volleyball players are susceptible to failure resulting from their own prior

negative performances – particularly under pressure. The finding would not be unique. Research has shown that negative plays more

than positive plays strongly influence players’ subsequent performance in the

PGA and NFL. The amateur status of

collegiate beach players, and the inability to substitute players, points to a

need for the development and use of mental skills interventions designed to

prepare athletes to perform in these circumstances and modulate the negative

effects of prior performance failure. Currently,

timeouts and game breaks provide players with a momentary opportunity to

mentally re-set after failure. But they

are short-term band-aids for a sports performance problem in need of a lasting

solution.

CONCLUSION

This study represents a novel foray into the complex

nature of serial dependency of performance.

Whether, and the extent to which, plays in beach volleyball are

dependent on previous performances remains an issue ripe for further

study. In particular, the psychological

mechanisms through which performance failure appears to portend further failure

and become magnified under pressure should next be studied at the individual

player level. Results could advance our

understanding of post-failure performance and inform the development of

training protocols useful to athletes in failure recovery. For athletes and coaches, the data can also

be a useful guide to optimal tactics in competition and predictive in exposing

opponent’s weakness.

Acknowledgments

The contributions of Shane Spellman and Ali Wood

Lamberson, who reviewed and improved an earlier draft of this paper, are

gratefully acknowledged.

Access and Use

A version of this paper is available for download in portable document format (PDF) here. No fee may be charged for access or use of this document or the information contained therein. The original copyright notice must remain on any downloaded and/or printed version.

Access and Use

A version of this paper is available for download in portable document format (PDF) here. No fee may be charged for access or use of this document or the information contained therein. The original copyright notice must remain on any downloaded and/or printed version.

[1] A

“hot hand” in statistical terms refers to serial correlation in positive

performance results beyond what can be explained by an athlete’s skill or by

chance alone.

[2]

Gilovich, T., Vallone, R. & Tversky, A. (1985). The hot hand in basketball: On the misperception of random sequences, Cognitive Psychology, 17(3), 295-314

(basketball). Otting, M., Langrock,

R.,& Deutscher, C., (2020). The hot

hand in professional darts. Journal of

the Royal Statistical Society. Society A, 183 (2), 565-580 (darts);

Morgulev, E., Azar, O.H., & Bar-Eli, M. (2020). Searching for momentum in

NBA triplets of free throws. Journal

of Sports Sciences, 38, 390-398 (NBA

basketball); Raab, M., Gula, B. & Gigerenzer, G. (2012). The hot hand exists in volleyball and is used

for allocation decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology,

18(1), 81-94 (volleyball); Clark III, R.D. (2005). An examination of the “hot hand” in

professional golfers. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 101,

935-942 (golf); Dumangane, M., Rosati, N. & Volossovitch, A. (2009). Departure from independence and stationarity

in a handball match. Journal of Applied Statistics, 36(7),

723-741 (handball); Klaassen, F. & Magnus. J. (2001). Are points in tennis interdependent and

identically distributed? Evidence from a dynamic binary panel data model. Journal of the American Statistical Association,

96, 500-509 (tennis).

[3]

Avugos, S., Koppen, J., Czienskowski, U., Raab, M., & Bar-Eli, M.

(2012). The ‘”hot hand” reconsidered: A

meta-analytic approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(1),

21-27. There is a growing body of

research finding fault with the statistical methods employed in earlier “hot

hand” research, effectively keeping the debate alive. Stone, D. (2012). Measurement error and the hot hand. The

American Statistician, 61, 61-66; Arkes, J. (2013). Misses in “hot hand” research. Journal

of Sports Economics, 14, 401-410. The hot hand has been analyzed in

non-sporting contexts as well including in hedge fund performance. See Jagannathan, R., Malakhov, A. &

Novikov, D. (2010). Do hands exist among

hedge fund managers?: An empirical evaluation. The Journal of Finance,

65, 217-255.

[4]

Scholarship on the cold hand is limited but includes: Arkes, J. (2016). The hot hand vs. cold hand on the PGA

Tour. International Journal of Sport

Finance, 11(2) 99-113 (evidence of cold hand in golf); Elmore, R. &

Urbaczewski, A. (2018). Hot and cold

hands on the PGA tour: do they exist? Journal of Sports Analytics, 4, 275-284

(evidence of cold hand found).

[5]

Graduate years (or class standing), are a reasonable proxy for collegiate beach

playing experience with the exception of graduate students. Graduate Students typically have 0-1 year of

collegiate beach volleyball playing experience.

[6]

Beilock, S., L. & Carr, T.H. (2001).

On the fragility of skilled performance:

What governs choking under pressure? Journal of Experimental Psychology.

General, 130, 701-725; Eyseneck, M.W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., &

Calvo, M.G. (2007). Anxiety and

cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7, 336-353; Gray, R. &

Allsop, J. (2013). Interactions between

performance pressure, performance streaks, and attentional focus. Journal of

Sport & Exercise Psychology, 35, 368-386.

[7]

Terminology is in-system (IS), out of system (OS), reception error or ace

(A). We could have used longer

sequences, such as three OS passes in a row, to define reception failure. Sequences of that length, however, are rare

in beach volleyball and so would have reduced the number of series and our

statistical power significantly.

[8]

When less than seven points were played on the final side change, we coded

plays during the last seven (7) points of the game as though they were

contested on the final side-change.

[9]

Our pressure model is adapted from Harris, D.J., Vine, S.J., Eysenck, M.W.

& Wilson, M.R. (2019). To err again

is human: exploring the bidirectional relationship between pressure and

performance failure feedback. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 32(6),

670-678.

[10]

Link, D., & Wenninger, S. (2019).

Performance streaks in elite beach volleyball – does failure on one

sideout affect attacking in the

next? Frontiers in Psychology,

10, 919-926; Raab, M., Gula, B. & Gigerenzer, G. (2012). The hot hand exists in volleyball and is used

for allocation decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology,

18(1), 81-94.

[11]

Gilovich, T., Vallone, R. & Tversky, A. (1985). The hot hand in basketball: On the misperception of random sequences, Cognitive Psychology, 17(3), 295-314.

[12] Klaassen,

F. & Magnus. J. (2001). Are points

in tennis interdependent and identically distributed? Evidence from a dynamic

binary panel data model. Journal of

the American Statistical Association, 96, 500-509.

[13]

Albright, S.C. (1993). A statistical

analysis of hitting streaks in baseball.

Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88, 1175-1183.

[14]

We acknowledge that service reception is influenced by characteristics of the

opponent’s serve and consider this a potential limitation of our findings since

we did not control for the difficulty of the serve. Nor do we think that attempting to do so

would have produced more robust results since “difficulty” is not susceptible

of objective measurement or definition.

Even had we decided to use speed, type and location of serve as

objective indicia of “difficulty,” we have no principled basis for determining

how the confluence of these factors would or would not establish the

“difficulty” of each serve. In any event,

the speeds of the serves we observed were not available and so could not be

included in our analysis. Our data

should be interpreted with this limitation in mind.

[15]

Harris, D.J., Vine, S.J., Eysenck, M.W. & Wilson, M.R. (2019). To err again is human: exploring the

bidirectional relationship between pressure and performance failure feedback. Anxiety,

Stress & Coping, 32(6), 670-678; Link, D., & Wenninger, S.

(2019). Performance streaks in elite

beach volleyball – does failure on one sideout affect attacking in the next? Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 919-926.

[16]

Beilock, S., L. & Carr, T.H. (2001).

On the fragility of skilled performance:

What governs choking under pressure? J. Experimental Psychology.

General, 130, 701-725; Eyseneck, M.W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., &

Calvo, M.G. (2007). Anxiety and

cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7, 336-353; Gray, R. &

Allsop, J. (2013). Interactions between

performance pressure, performance streaks, and attentional focus. Journal of

Sport & Exercise Psychology, 35, 368-386.

[17]

Sagar, S.S., Lavallee, D., & Spray, C.M. (2009). Coping with the effects of fear of failure: A

preliminary investigation of young elite athletes. Journal of Clinical Sports Psychology,

3, 73-98.

[18]

D.J., Vine, S.J., Eysenck, M.W. & Wilson, M.R. (2019). To err again is human: exploring the

bidirectional relationship between pressure and performance failure feedback. Anxiety,

Stress & Coping, 32(6), 670-678

[19]

Elmore, R. & Urbaczewski (2018). Hot

and cold hands on the PGA tour: Do they exist? Journal of Sports Analytics,

4, 275-284.

[20]

Carson, H.J. & Collins, D (2015). The fourth dimension: A motoric

perspective on the anxiety-performance relationship. International Review of Sport and Exercise

Psychology, 9, 1-21.

No comments:

Post a Comment